Bach’s Classical Pop

In my ongoing search through the archives of classical music there’s one question I keep asking myself: Why is almost all of it so un-catchy? In Amadeus Emperor Leopold rebukes Mozart: “Too many notes.” The Emperor is right. The overly busy melodies of so much classical music are a real source of exhaustion and annoyance. Such overwrought musician’s music has no charm. It merely expresses a hollow kind of “skill” and offers no delight to the listener. Until Beethoven, with a few shining examples, classical composition was out of touch with the listener.

In all the forms, the pieces go on too long. The listener gets tired. “The listener be damned!” say the composers. We complain today of how there’s too much image involved in music. It started in classical. The focus on the virtuoso turned music into a circus, an also visual experience. This could account for the emptiness of many classical works when listened to on a stereo. There’s a necessary visual component that is missing. We’re left with the music itself and without charm or discernable melody it’s not enough. We take the concept of recording and stereo playback for granted. Until Edison composers had no such concepts. Music had to be performed or experienced imaginatively through sightreading. The idea of repeated playback was hence not part of the classical composer’s thinking going in. For this reason there’s a tendency toward the flashy, and away from the catchy. I attempt to establish the rule so I can focus on the exceptions. In my ongoing archival search I find flickers of the irresistible, very sporadic instances of high catchiness, stuff that very much unfolds in a modern pop way, that builds to a chorus. One of these exceptions, these glimpses of classical pop that I’ve recently become enamored with all over again is Bach’s Air on a G String.

It can be hard to step back far enough from such a classic to really hear it as its initial audiences did. Remember, Bach’s Air on a G String was once new. We have to time travel. We have to step back from it, remove it from our subconscious. I have tried to do that and listening to it over and over recently I have to say I can hardly contain my admiration for this work. I was once given a CD of Bach’s “fugues” – these elaborate solo organ pieces. They annoyed the hell out of me. The Air is another story.

What tempo! What slowness! Bach makes baroque stateliness a thrilling ancient rhythm. This is a slowness that envigorates. The song is a calm musical act, but out of that calm such passion, such utter higher beauty takes off. The Air boasts Bach’s most exquisite, most maximized melodies. Schopenhauer explained where music comes from. It comes from the earth. Bach’s strings come from the clouds. The whole bow moves back and forth across the strings. A note can go on forever because the percussion is built in. The bow’s sudden reversal is a subtle form of the snare drum. He weaves his gorgeous lines, one taking off after another like a round. His melody layer effortlessly achieves uncanny emotional resonance (‘it sounds like a feeling’). Bach tells the story of his passion for the G. From the very beginning he keeps his violin on one note over the classic descending bassline. As the bass descends it continually recolors that one violin note in such a pleasing way. It’s the essence of beauty in music, the essence of catchiness. The major key is pronounced and infinitely sustained throughout the work. Never drop that beautiful note, just add other notes to it. This is how the ear falls in love.

While the Air plays I lean back and consider the pettiness of my everyday thinking, the triviality of my life. What really matters is up there, in the heavans promised by Bach’s Air. We float up above ourselves, lifted by music at the limit of its powers. Your room becomes a shrine. Your friends become the exalted few.

For Bach undoubtedly the composition of the Air was effortless and quick, and thus he may have distrusted its quality, but Bach can be most proud—centuries have passed and it’s still getting better.

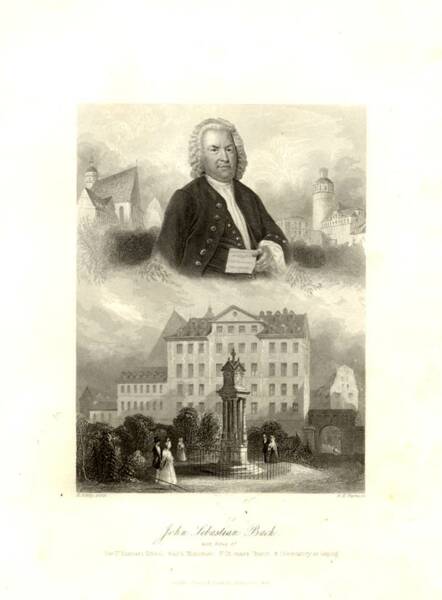

Johann Sebastian Bach

Lombard Antiquarian Print c. 1840